One of the challenging facets of curriculum design is offering students the widest range of choice possible, without creating impossible programmes.

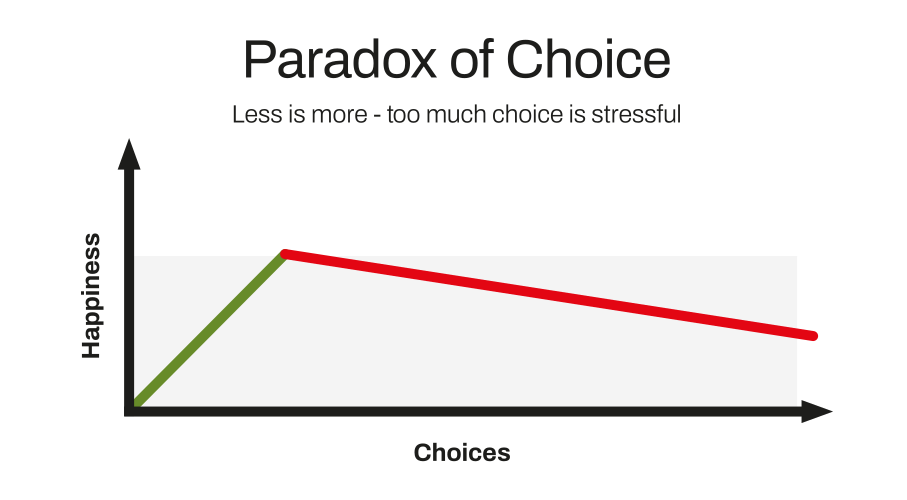

While a healthy range of options is essential, there is a point at which the scope of choice tips from positive to negative – the paradox of choice. This states that while we might believe that being presented with multiple options makes it easier to choose one that makes us happy and increases our satisfaction, in fact, having an abundance of options requires more effort to make a decision and can leave us feeling unsatisfied with our choice. In scheduling, it can also lead to untenable combinations of resources for minimal student numbers. So where do you find the balance?

How much choice do our students want, anyway?

Having too many choices creates anxiety and leaves people less satisfied, says American psychologist Barry Schwartz in his 2004 bestseller The Paradox of Choice. He cites a Stanford University study, which asked volunteers to choose from a box of chocolates and gauged their satisfaction:

- The unhappiest were those with no choice at all – all the chocolates were the same flavour.

- Those who chose one chocolate from a range of 30 different flavours, also weren’t sure they’d made the right choice, and worried they were missing out on something better.

- The happiest were those who chose one from a limited range of six flavours. They found the ‘sweet spot’ on the graph below.

“The Paradox of Choice – Why More Is Less”, Barry Schwartz, 2004.

Complexity breeds Complexity

Since 2020, we’ve all become too familiar with diagrams illustrating exponential growth. It’s easier nowadays to see and explain the detrimental impact of ‘unstructured choice’ in curriculum design. Exhaustive lists of elective modules simply lead to broken promises, clashes, fragmented timetables, strained schedules, poor deployment of resources, and ultimately to both staff and student dissatisfaction. How do curriculum designers find the sweet spot?

The ‘1 from 6’ rule works quite well in mathematical terms, when applied to curriculum planning.

Here’s a simple example. Imagine your LLB Law, Year 2, has a list of 12 optional modules. Students are permitted to choose any two of them. That creates 66 possible module combinations. All of these must be kept clash-free in the timetable, just in case somebody chooses that combination. There aren’t enough hours in the week to accommodate it all. Without question, some modules will end up clashing, some choices will be denied, causing dissatisfaction.

However, if that list of 12 optional modules is reframed so that students are advised to pick ‘1 from the 6 in List A’ and ‘1 from the 6 modules in List B’… That creates only 36 possible module combinations. This is much easier to accommodate clash-free in the timetable. It also offers an element of hidden guidance by eliminating the unlikely/pedagogically inadvisable combinations. Students are more likely to have a clash-free timetable, first time. The timetable remains more stable.

In mathematics terms, the actual formula is:

.png?width=714&height=177&name=Paradox-of-Choice-2%20(1).png)

[the number of possible combinations where a student needs to choose r out of a total of n]

Takeaway

FOR SENIOR MANAGEMENT

You offer an illusion of choice; much of what is promised in course handbooks cannot be delivered in practice. We can show you how to deliver those promises.

FOR PROGRAMME DIRECTORS

If you reframe your optional module choice, the timetabling team is more likely to deliver your promises. We can help you to model this.

FOR TIMETABLERS

No question that your job has got more difficult over time! We can help you to illustrate where the pinch points are, model alternative scenarios, and deliver a more efficient timetable.

RESULT: The right schedules, for everyone.

Anne Johnson has 25 years of experience in the Education Sector including management positions at leading UK universities and timetabling systems consultancy in the UK, Europe, and the Middle East.