As a principle of business strategy in any competitive market, success is typically built on knowing what you are good at and succeeding in one, or at most two, of three dimensions; be it high volume low margin efficiency; or customer intimacy in persuasive differentiated services; or innovative high quality product leadership. By virtue of their history and public purpose, TAFEs (Technical and Further Education) however have a multidimensional challenge. The expectation of their role as a ‘public provider’ is to be excellent in all these dimensions, whilst being ‘arms-length’ yet (part) tied to objectives, resourcing and desired outcomes as maybe directed by their public-ownership.

TAFEs’ performance is then expected to be multi-facetted and equally excellent in all dimensions. Here are illustrative examples: delivering training in the remote outback to indigenous communities; English language and culture for migrants; job and life skills through training of city kids from families with intergenerational unemployment; winning private revenue by contracted training with firms across a wide array of industry sectors; attracting and delivering high quality programs and ensuring welfare of fee paying international students; getting best utilisation of aging sprawling campuses whilst being increasingly competitive in high volume lower margin courses by on-line delivery; and for the majority of their domestic students delivering quality VET and career-customised support all linked to school and university pathways and employers.

Public provision thus spans all of public and social good in helping less prepared vulnerable students, in running courses in regions or in niche skills not otherwise viable, as well as being in the vanguard of state and regional economic development in advanced technology in curricula and teaching tools like virtual or augmented reality. One consequence is TAFEs’ registered scope of qualifications is typically far larger (than private Registered Training Organisations (RTOs)). This raises the regulatory bar in sustaining TAFEs’ branding and reputation as a benchmark for quality.

Given the present set up of VET in Australia’s ‘tertiary education system’ (with universities and multiple private RTOs), is this view of TAFEs being ‘comprehensive and excellent in all dimensions’ operationally and financially sustainable? Given global disruption to traditional ‘business models’ of educational services, and with student/industry demand steering towards ‘just in time, just what’s needed now’, how can TAFEs win even more prominent part of any future ‘tertiary system’ landscape. Not just because of their size, public purpose and tradition, but by building on their history in farsighted leadership in course/credential content and delivery modes that best meet needs of ‘future jobs’, employers and students.

Similarity and Diversity Among TAFEs

Following ‘structural adjustment’ incentives in the National Partnership for Skills Reform, with the exception of Victoria, governments moved to aggregate colleges under typically State-enacted Statutory Corporations . In the view of some, TAFEs have been subject of protracted and major adjustments and distractions from their core purpose - quality training and education - in the name of ‘markets, competition, contestability and corporatisation’.

Major aspects of commonality of all TAFEs include the Australian Qualifications Framework (AQF), international student visa rules, competency and training package qualifications (with some differences in accredited qualifications with Victoria and Western Australia retaining local regulatory rights), common/like regulatory legislation and like access to Commonwealth financed VET Student Loans at Diploma/Advanced Diploma levels. All States and Territories are funded under the National Agreement for Skills and Workforce Development, and all but Victoria and Queensland having contracts under the Skilling Australians Fund (only South Australia and Western Australia have multi-year agreements).

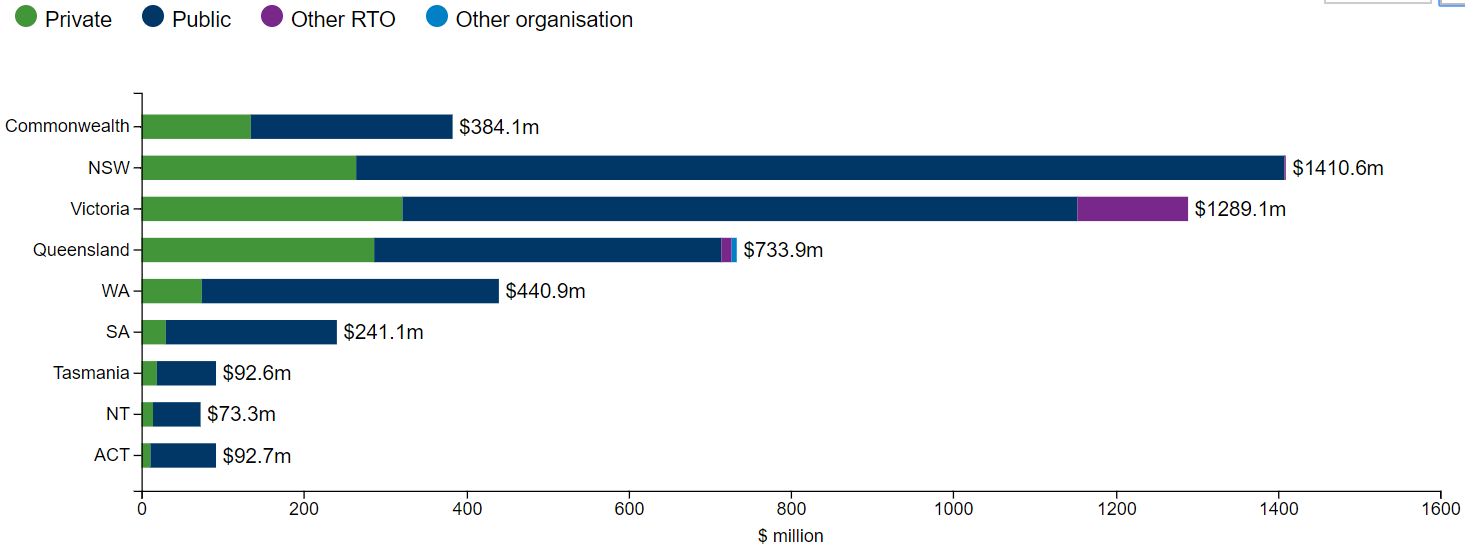

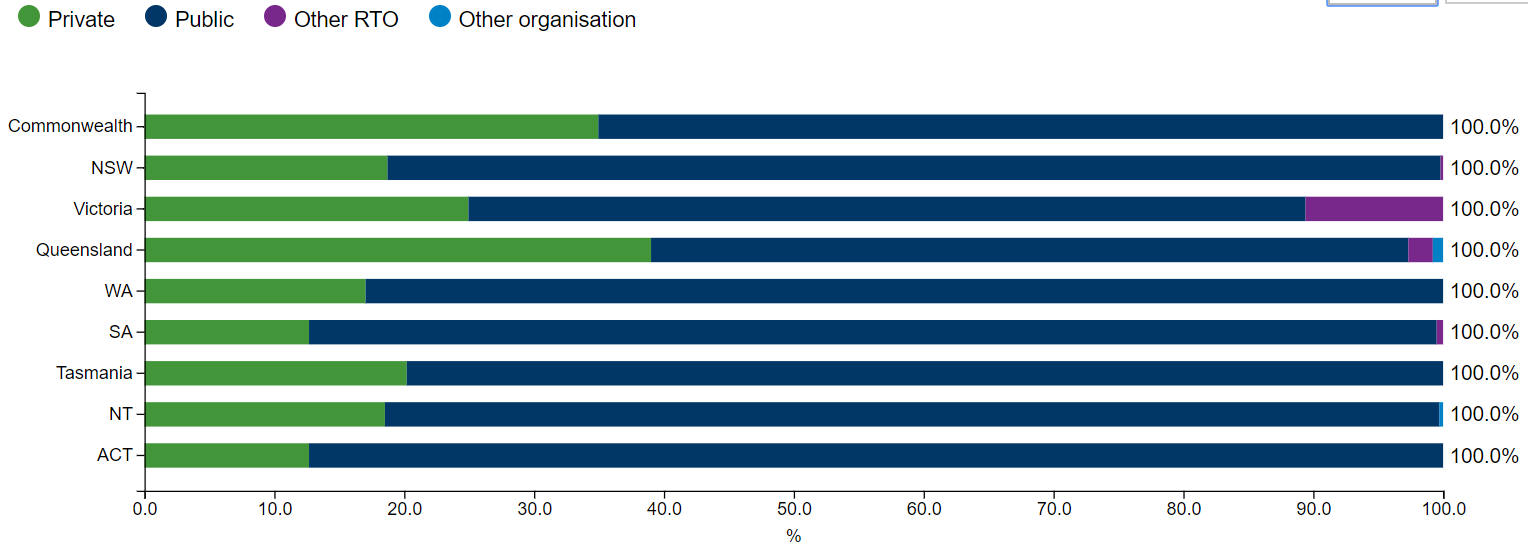

By contrast the major differences across TAFEs relate to prevailing economic, social and operational context. They cover vast geographies with sprawling campuses in cites and sometimes shared (e.g. with schools and universities) facilities in regions, often seen as community assets, all with maintenance costs that might be better spent in a ‘digital-delivery’ world. They serve very different state and regional economies and communities. TAFEs are subject to differing State/Territory VET contestable policies and funding, much dependent on a government’s view point and jurisdictional resource capacity. Figure 1a shows all sources of government funding in 2017 by RTO type ($) and 1b (%).

Figure 1a: Government funding of VET 2017 – VET funding by RTO type $m (NCVER)

Figure 1b: Government funding of VET 2017 – VET funding by RTO type $m by % (NCVER)

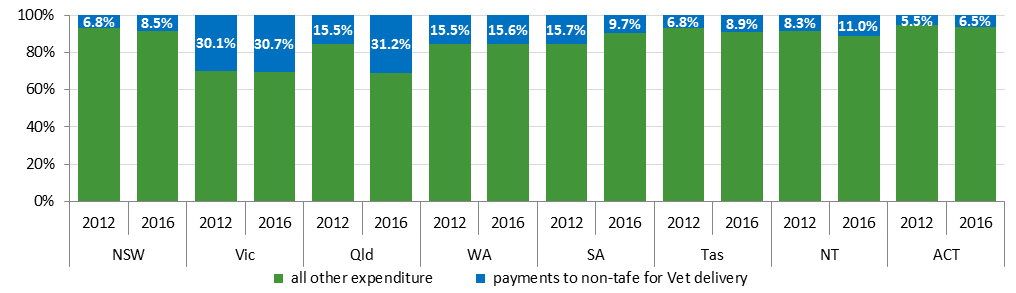

Figure 1c - State and territory payments made to non-TAFE providers for VET delivery as a component of total operating expenditure for latest years 2012 and 2016 (NCVER)

Figure 1c compares differences and shows trend changes between 2012 and 2016 in State and Territory payments to non-TAFE providers as a proportion of total operating expenditure. In absolute terms compared with schools and higher education, VET has shown a steady trend decline in public funding. National funding has not only declined but also been subject of contested cost shifting from States and Territories to the Commonwealth for five interrelated policy reasons. Some jurisdictions have both the political will and capacity to inject funds to help rebuild TAFE infrastructure e.g. in Victoria and fund some TAFE fee-free courses/apprentice programs, e.g. Victoria, New South Wales, Queensland.

By way of comparison with private RTOs, TAFE’s industrial agreements are seen as a major reason for TAFE training being more expensive than the equivalent private training. TAFE’s students and course profiles do differ from private RTOs, the latter tending to provide less resource intensive courses with TAFE dominating in more resource intensive programs needing far more complex facilities and fixed infrastructure.

Pragmatic voices hold highest an uncompromising VET quality agenda, regardless of provider. Student and industry surveys do not, in the broad, show differences in training quality, completions, nor job benefits between TAFEs vs private RTOs. The VET sector needs an unrelenting quest for quality and relevance, with TAFEs as public providers to set highest benchmarks for quality beyond just compliance.

TAFEs also compete with universities for students at a significant policy and financing disadvantage. Students are easier enticed into universities. TAFEs must then build articulation and credit transfer arrangements with ‘competitors’ across sometimes awkward sectoral boundaries, or more valuably work dual sector, and/or seek advantages from a ‘shared-campuses’ in regional settings. Such partnerships between universities and TAFEs or TAFEs and industry are locally negotiated. Finally TAFEs are urged to ride the revenue wave of international students, on and off shore, again linking with university partners.

Consistent demonstration of TAFE’s public benefit and financial sustainability

To their great credit many TAFEs do consistently achieve in all these dimensions. But they are under immense challenge to deliver on their multi-dimensionally public benefit with economic, social and regional value and impact, as well as being financially sustainable. A number of TAFEs have recently reported operational (at least accounting) deficits including major cost overruns in information management.

The risk is some TAFEs in time may flounder much like an old fashioned department store struggling to be ‘all things to all people’. An alternate positive vision is a dynamically operating and widely partnered entity, having a multi-skilled educational and training services warehouse with super-smart logistics, packed with customised high quality contemporary products, all delivered to almost anywhere as needed.

If the latter vision is one road to the future, there is need for each TAFE to create and drive a renewed strategy, structure and culture. Essential to this is deep understanding of all parts of its business in integrated data and business analytics, with informative benchmarks to suitable peers.

The VET sector will now look to implementation of the Joyce Review of VET as funded in the recent national budget. The present review of the QF will in all likelihood expose the need for a more coherent, federally supported and nationally operating tertiary funding framework across its qualifications. From TAFE’s perspective, the review of the Higher Education (HE) Provider Category Standards may lead to a sharper distinction of the roles of non-university HE providers in for example aspects of their industry engagement. This would also ideally lead to policy reform unpicking the present differences in operational autonomy and funding/financing that so advantage universities and disadvantage TAFEs.

To see how TAFEs can use benchmarking techniques to drive this renewed strategy, structure and culture, join our latest webinar; The role of benchmarking in Australia's TAFE sector.

TOPICS:

SHARE THIS ARTICLE: